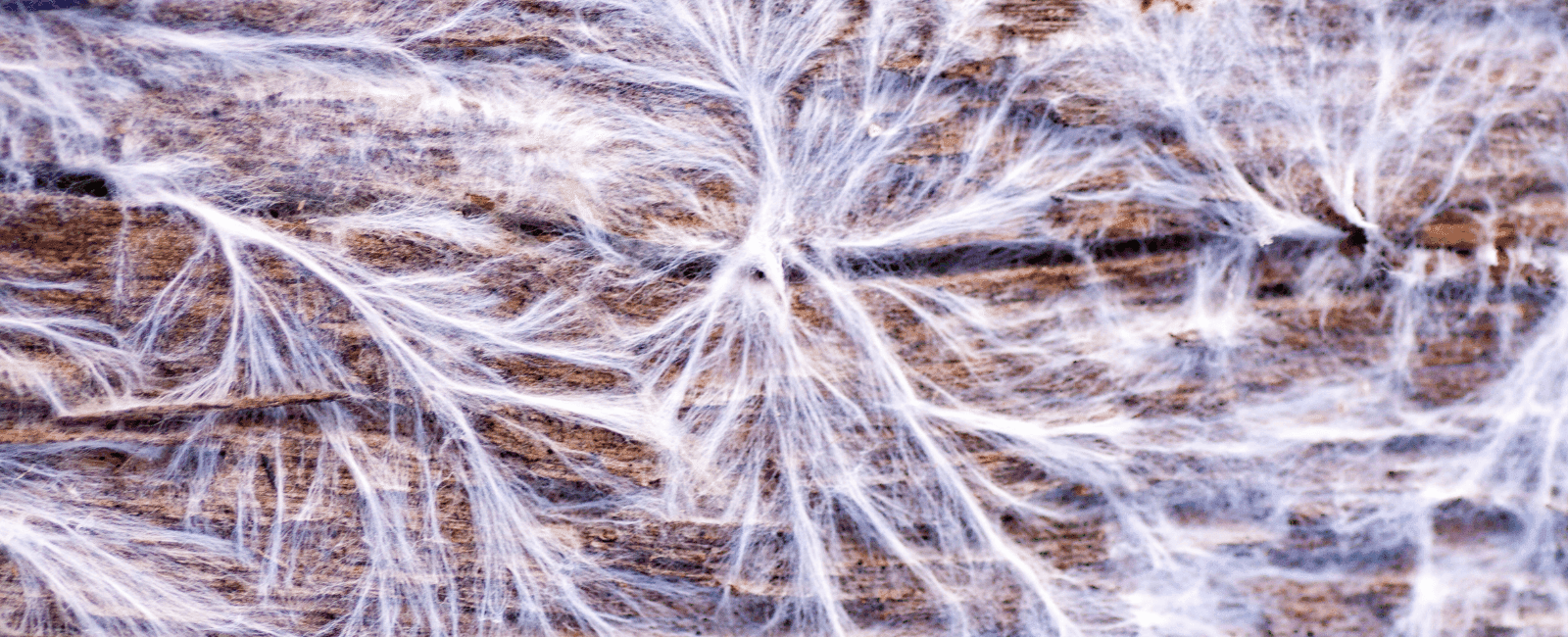

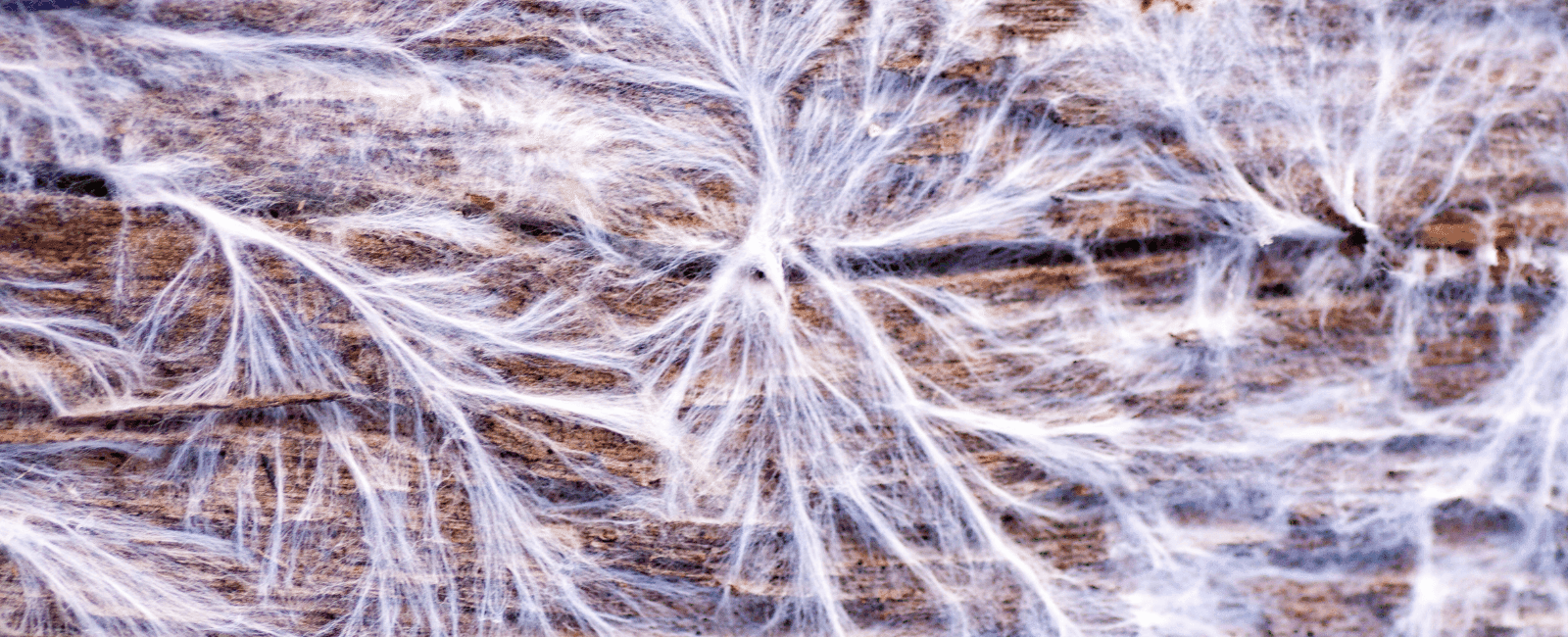

Let’s go beyond the fruiting bodies of fungi and learn about the real star of the show: mycelium. Not all mycelia produce mushrooms, but mushrooms serve as an excellent example of how mycelium functions. When we look at a mushroom in the ground, we only see a small portion of the entire organism. Mycelium can grow deep inside wood or in the organic substrate of the forest floor. Think of it like the roots of a plant – mycelium spreads into the ground as tiny branching filaments called hyphae. These fungal roots can spread at great distances, increasing the size of the fungus and the surface area it covers.

Hyphae produce enzymes that break down organic matter, then transport the nutrients into an absorbable food source for fungi. However, mycelium has many purposes outside of converting nutrients for a fungus to grow. By breaking down organic matter, they recycle biomass and aid soil fertility. Mycelia play a vital role in maintaining healthy habitats, yet some go beyond their decomposer duties and actively benefit the living organisms around them.

What is the mycelial network?

The mycelial network, otherwise known as the mycorrhizal network, is an interconnected system between mycelia and plant roots that joins different plant and fungal species within an ecosystem.

Although mycelia always break down matter and provide nutrients to fungi, not all of them function within the mutually dependent network. Only mycorrhizal fungi can form a symbiotic relationship with other fungi and plants. About 10% of all fungal species identified today fall under the mycorrhizal category, yet these unique fungi are crucial to ecosystem health (1).

The benefits of the mycelial network

Fungi communication

As crazy as it sounds, fungi communicate through their mycelial networks to warn each other of danger and adapt to changing environmental conditions (2). Studies have found that fungi respond to internal and external indications of threats by sending out nutrients and electrical impulses through the hyphae (3).

When a fungus senses a potential danger, it can react by sending signals through the thousands of hyphal pathways that make up the mycelium network. These signals warn the fungi within that network about potential predators or environmental changes, such as limited water resources. As a result, other fungi can adapt to the warning or transfer nutrients to each other to stay alive.

Other plant communication

In addition to supporting other fungi, mycorrhizal fungi greatly support the many different species of plants within the fungal network. These fungi connect surrounding plants as the hyphae wrap around their roots. Although the fungus essentially takes over part of the plant, the two form a symbiotic relationship that allows them to benefit from their arrangement.

The fungi transport nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus while assisting the plants with their water uptake. Moreover, the complex network protects plant life from pathogens by warning them at the first sign of danger (4). In exchange, the fungi feed on the plant’s sugars produced during photosynthesis.

The “wood wide web”

Mycelial networks also allow plants to communicate with each other. Since the fungi links to surrounding plant life, it utilizes its thousands of hyphae signals to transfer information and nutrients. This network connecting all plant life in an ecosystem is known as the “wood wide web” because it allows communication between otherwise separated plants. This system benefits forests by allowing trees to transfer information and nutrients amongst each other.

Evidence supports that many trees will pass on nutrients to their children through the network to help them survive. Such connections allow plant life to thrive off of each other and survive attacks from pathogens and pests that could wipe them out. The networks that connect plants provide an effective communicative means that otherwise couldn’t exist without the fungi’s help.

Specific uses of fungal mycelium

The benefits of fungal mycelium exist beyond the forest floor and make their way into our households and daily life. Mycelium grows at such a fast rate, which allows a cost-effective, natural means to produce different kinds of goods. Mycelial fibers are used for a variety of reasons:

- Mycelium can filter concentrations of pollutants and microorganisms from contaminated water or soil (5).

- The water resistance and fireproof properties of mycelium make it an excellent building material or an insulation replacement for environmentally hazardous fiberglass.

- Mycelium provides a vegan alternative to leather with a similar appearance and durability when compressed.

- Vegan “meat” made by mycelium has gradually gained popularity because of its striking textural resemblance to actual meat.

Since mycelium is a biodegradable natural resource, it is an excellent replacement for less sustainable materials. Its versatility gives us more ecologically friendly alternatives to explore throughout different industries. Mycelium also is non-toxic and safe for human health, making it a preferable option for packaging, housing, food, and clothing.

One of nature’s most essential tools

Though mycelium stays hidden underground, outside the spotlight, it’s one of nature’s most essential tools for maintaining a balanced ecosystem. Mycelium’s ability to connect plants and fungi demonstrates its complex role in the environment. The fast-growing fibers decompose waste, support plant life, and produce a natural material for several different needs. Mycelium makes up the bodies of fungal organisms, stretching throughout forests to provide their symbiotic benefits.

Shockingly, the largest living organism on earth is actually a fungus in Oregon that has grown to span around four square miles! Think about just how far of a reach mycelium can have as it spreads through the ground through each of the different fungal colonies. Microbiology is an incredible field of study, bringing to life the ecology around us, from the cell walls of our very bodies. When you go outside, take some time to appreciate the hidden mycelial world that exists beneath your feet and how it impacts the nature around you.

References

- Stefanie S. Schmieder, Claire E. Stanley, Andrzej Rzepiela, Dirkvan Swaay, Jerica Sabotič, Simon F. Nørrelykke, Andrew J. deMello, Markus Aebi, Markus Künzler, et al. “Bidirectional Propagation of Signals and Nutrients in Fungal Networks via Specialized Hyphae.” Current Biology, Cell Press, 3 Jan. 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982218315574.

- Mnkandla, Sanele Michelle, and Patricks Voua Otomo. “Effectiveness of Mycofiltration for Removal of Contaminants from Water: A Systematic Review Protocol - Environmental Evidence.” BioMed Central, BioMed Central, 28 July 2021, https://environmentalevidencejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13750-021-00232-0#:~:text=Fungal%20mycelium%20are%20said%20to,xenobiotics%20%5B9%2C%2010%5D.

- “Mycorrhizal Fungi.” Mycorrhizal Fungi - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/mycorrhizal-fungi.

- Marcus Roper, Emilie Dressaire, et al. “Fungal Biology: Bidirectional Communication across Fungal Networks.” Current Biology, Cell Press, 18 Feb. 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982219300132.

- Underground Allies: How and Why Do Mycelial Networks Help Plants Defend … https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309827892_Underground_allies_How_and_why_do_mycelial_networks_help_plants_defend_themselves.